For those interested in trying it out, a few thoughts on first person living history:

First person interpretation is

pretending to be a person from the past—and not alluding

to the fact that you are a twenty-first century person in funny

clothes talking about the past.

We call it

"first person" because you are using the grammatical first

person ("I/me/my, we/us/our") to convey your information. For example:

First

person: "I

fear prices will keep

rising as long as the blockade lasts."

"We

are making a quilt for the hospital."

Second

person: "If

you

lived here in 1855, you'd

be sharing this one room with all of your

siblings."

Third

person: "He

wrote most of his letters at this desk."

"The

soldiers often

complained of inadequate rations."

"They

didn't have electricity."

In first person,

the speaker is placing himself or herself in the past. In second,

the person being spoken to is placed in the past. In third person,

the person(s) being spoken about is(are) placed in the past.

How to do it

In short, start using "I" statements. Everything you

already know and share about the period is still relevant—you're

merely changing how you present the information.

There are two main groups of people you'll interact with in first person: other reenactors (in first person), and the public (people not in first person). Most of the techniques are relevant to both, though the later group in particular may need some prompting to understand that you are from the past--in first person rather than in third. You'll also get the occasional corny attempt at humor ("Where's the TV?"; Waves cell phone--"Have you ever seen one of these?"); I prefer to handle these with a polite smile, "I am unfamiliar with that term", and getting back on topic.

It's fun to do first-person with other reenactors, and you don't need to

plan out elaborate scenarios and scripts. At the bare minimum, all

you need to have worked out is that you're in the same place—knowing

where and when you are.

When are you? Where are you?

Some events make this clear in

advance: the event and everyone at it is in Gettyburg, PA July 1-3,

1863, for example. Others events are less well-defined, in which

case you need to either work out your location/date or avoid using specific (time-sensitive) details that might not fit. Discussing the upcoming presidential

election is an excellent topic for the summer of 1864, but makes less

sense if your conversation partner thinks its the spring of 1861 and

was just about to bring up their thoughts on the recently-past

election. Complaining about blockade-caused shortages as a Georgian

in 1863 is great...that is, if you're not talking to a northern

shop-keeper who's noticed no such hardships, or to your southern

neighbor of '61, who's still anticipating a quick war after First

Manassas.

Dropping the year into your conversation can also help orient the public to your first-person conversation. Ie, "Look at our new cook stove. Poor Thornhill was actually cooking over an open hearth until it arrived last year--imagine cooking on a hearth in 1854! But then, with the expense of shipping it around Cape Horn, we're quite lucky to have it at all."

Who are you?

Unless you're

at a planned event where you share a backstory with other people--who

are portraying your close friends, family and neighbors--this sort

of background information is largely for your own benefit. It's both

very important (your persona's social, political and geographical

background informs everything you say/think/do in character), and not

very important (unless you bring it up, no one will ever ask about

your character's childhood home, or deceased relatives, or favorite food).

To start, work out the very basic concepts such as your name, your

relationships to other people present at the event (if any), and what

you're doing there. You can build a more elaborate persona as you

feel comfortable with it.

Introduce yourself!

Use a

period form of introduction to do so, and you're already in first

person.

Keep Talking, Keep Trying

Venture an opinion: on the weather, on the shop-keeper's prices, on

that bonnet you saw in Godey's, on the President's recent

proclamation, on the war, on a patent medicine you tried. Ask a

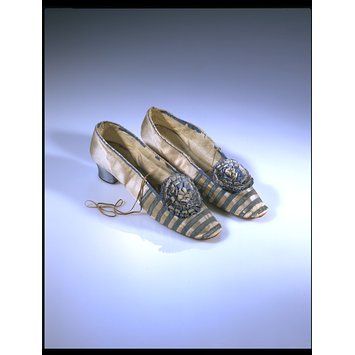

question, How's your health? Where's a good place to buy shoes? Have you

seen my husband pass this way? What do you think of the military

occupation/weather/recent political event/lastest fashion fad? Have

you seen the latest edition of Harper's? Tell an amusing anecdote.

Offer advice. Anticipate a coming event: the ball tonight, the end

of the war, your sweetheart's next letter. Discuss your day/the

children/that new Dickens novel you're reading. Attempt to recruit

your conversation partner into some future project: planning a

charity ball, supporting a political candidate, investing in your

land speculation scheme.

I find first-person opportunities provide excellent fodder for your

next first-person encounter: discussing the last ball over

dinner, or recounting the time that the maid

tripped and invented "flying aspic". If you interact

with the same people, you'll also start to develop shared stories and

backgrounds which can be referenced on future occasions.

Period literature can make a pleasant topic of discussion. Incidents

and opinions found in period diaries, letters, and travelogues can

also be adapted for personal use: for example, one lady at Nisqually last year

portrayed a character who had crossed Panama by mule, and regaled us

with stories of the trip. Avoid taking well-known incidents and putting yourself into them—unless you actually are

portraying one of the Pinkerton agents who thwarted the first

assassination attempt against Lincoln (or whatever the particular

situation is).

Do Something/ Start Conversations

This applies to in-character interactions as well, but it's vital to conversations with the "public". Visitors don't always know that

you're in character, and might not know how to approach you. even if they do. Doing something provides one way to break the

ice—the public can ask questions about it, or you can greet them and volunteer information about your activity.

This is also great for you, as it focuses the sort of questions you'll

be getting. Even if you don't feel like you know everything a person

from you period would know, you can research a narrow topic until you

feel comfortable with it (most people aren't looking for a

dissertation). So, read up on period laundry methods if you're

washing clothes. Consider where you bought/procured the food you're

cooking with. Know who you're writing that letter to, and be able to

name the equipment you're using to write it. Someone who sees you cooking is more likely to ask you a question or two about your menu/tools/where you acquired your ingredients--ie, the questions you're prepared for--than to grill you for minutiae on politics, or transportation, or fashion.

Then, when a visitor comes up to you, start talking to them. I like

to start with a "good morning", or "good afternoon"

("hello" seems to be uncommon in 1860s, and "hi"

is right out). The visitor will often ask when I'm making/doing, and

I can explain that I'm tatting/rolling gingerbread/sewing a skirt.

If they don't ask another question, I can offer a few more details

(tatting is a sort of lace-making; I'm using it to make a decorative

trim for a chemise, which is a sort of undershirt that keeps my other

clothing nice). Eventually, the visitor will either start helping

carry the conversation, or they will take their leave. Either way,

you've just taught them something. And you did it in first person!

Admit That You Don't Know

This where I most often end up

breaking character. Someone asks a question, and you don't know the

answer. The cardinal rule of living history and museum

interpretation is do

not

make

it

up.*

So, don't. Own up to your ignorance. Offer what relevant

information you do have. If it's something that can be handled in

character, great—after all, there are things your character

wouldn't know. If that's not the case, ie, the question is one that

your character should be able to answer, then you need make it clear

that you're breaking character when you say no. And later, you can try to find the

correct answer for next time.

Some ways to answer in character:

"I've no idea what the clerks are paid, but it's surely more than I earn picking potatoes. Are you looking for a

position?"

"My maid handles the laundry. I don't know how she gets those

ink spots out, but my undersleeves always come back neat and clean.

Nevertheless, I've started wearing sleeve protectors when handling a

large correspondence."

"How old's the wheat? Well, I planted it late spring, and it's ready to harvest now, and that's my main concern." [If the questioner persists in asking about the dates for the wheat variety, I'd break character to say that I don't know.]

To gracefully demur: "Actually, I don't know how much the seasonal workers were paid, but we're continuing to research the topic. I do know that servants in this area earned around $X per month, and expect that unskilled labor was paid at a similar level."

Keep Learning

The more you know, the more... Questions you can answer.

Conversations you can enjoy. Interesting scenarios you can devise.

Different personas you can try.

The more accurately you can present the past to others.

Some resources for developing more advanced personas and research:

Resources from the Atlantic Guard Soldiers' Aid Society

Linda Trent's

"Creating Believable and Sustainable Characters"

First Person Character Worksheet

Discussion: Staying in First Person

In the Right Mind part I

In the Right Mind part II

To Re-Cap

First person interpretation is pretending to be someone from the past—using "I" and "we" in your conversations.

When doing first person with other reenactors:

Know who, where and when you are

Introduce yourself

Keep trying

Continue to learn

When doing first person interactions with the public:

Know who, where and when you are

-

-

Admit when you don't know the answer (stay in character if you can)

-

*To clarify, yes, you are lying: first person is a mutually-agreed-upon-fantasy, in which everyone knows that you were not actually born in 18XX, but both you and the visitors are pretending otherwise. All liberties need to be confined to this 'mutual fantasy' dressing and not get mixed into the history itself. We're here to educate, and inventing 'facts' does a disservice to everyone (including future generations of interpreters who get to keep disabusing returning visitors and their grandchildren of stories—that have no basis in fact—invented by previous living historians). The public is are trusting you to tell them what the past was like, and are granting you license in the presentation. So, go ahead and relate the funny privy story you read (in a period source) as though it happened to you, or use your own experience with the horsehair sofa as a warning about sitting carefully (happened while using period items in the prescribed way), but don't invent something out of wholecloth and pass it off as history.