I'm treating men's and women's stockings and socks together, as extent examples are rarely differentiated. Cotton, silk, wool, and linen stockings are all found in museum collections, while period literature mentions silk, cotton, and wool frequently. These were available for sale in a variety of colors, styles, and sizes, with home manufacture by hand or by machine also possible.

According to

"Manufactures of the United States in 1860" (U.S. Government, 1865), stocking frames had been used in the U.S. since 1723, with a mechanized version invented in 1832. Circular frames (allowing a stocking to be knit without a seam up the back) arrived in 1835. By the end of 1863, the U.S. had issued 126 patents for various knitting machines and improvements, including both models for use in homes and in factories.

The power knitting frame improved productivity by up to 150-fold: a worker who turned two pounds of cotton into stockings each week now handled 300 pounds of cotton in the same time. From June 2, 1859 to June 1, 1860, factories in the United States produced some 1,447,200 pairs of stockings, as part of a hosiery industry using 2,927,636 pounds of wool and 3,982,342 pounds of cotton annually. This commercial production was fairly equally divided between New England and the Mid-Atlantic States, with little in the West and none in the South.

When knit by hand, stockings could be made in a single piece, shaped by adding or subtracting stitches as the knitting progressed (some early

machine-knit stockings had the increases and decreases worked by hand, too). Another option was to knit the material into a (seamless) tube by machine, then cut and sew it into shape. Alternatively, stocking could be made out of flat knit fabric; two pieces are cut and joined together: a welt which goes under the foot, and a main piece which covers the top of the foot, wraps around the heel, and also comprises the upper portion. The wool stockings below show seams consistent with this style of construction.

|

| Wool stockings, c. 1860-70, from The Met |

Another option is to sew stockings from woven cloth, specifically from old wool garments. This method, though economical, is rarely mentioned.

The American Family Encyclopedia (1856) tells us that "although the stocking loom has, in a great measure, superseded the use of the knitting needles, the latter are not entirely laid aside; and stockings knitted by hand, though generally less beautiful in appearance, can be more depended upon for durability as well as for accurate fitting." This is borne out by the patterns available for

knitting socks and

stockings by hand (or, less often, for crocheting them), and by the inclusion of

knit stockings in school needlework curricula.

Knitting machines or stocking frames were also marketed for at-home use.

Nonetheless, ready-made stockings came in a variety of materials, styles, and sizes.

This encyclopedia names the "usual sizes" as "childrens', girls', maids', slender womens', womens' full size, [womens'] large size, boys', youths', mens', men's out size, gouty hose, fishermens' hose". Both socks and stockings are commonly available in silk, spun silk, silk with cotton feet, cotton, worsted [smooth and tightly spun wool], lambs' wool, etc. There are even light "gauze hose" (cotton and worsted) to be worn under the silk stockings.

|

Striped cotton stockings, red and white

c. 1850-70, from The Met |

Striped stockings were popular for women's wear in the early 1860s (and

one source suggests they were "purloined" from men's fashion). When only part of the stocking is decorated, it is most likely to be either up the sides of the ankle, or over the top of the foot and ankle (even up the leg to the mid-calf).

|

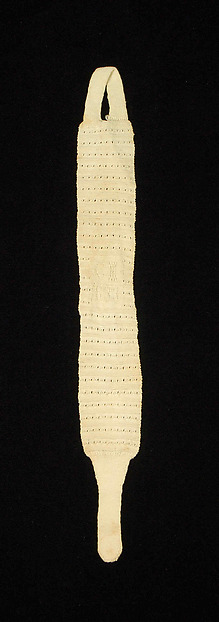

"Openwork" cotton stockings, c. 1860-70

from The Met |

In 1864,

Peterson's tells us that:"Stockings will be worn colored this winter; the silk stockings with narrow stripes around them are very suitable for this season of the year; the ground of the stocking should match either the dress or the petticoat in color. Merino stockings are also manufactured in brilliant colors--violet with black stripes, gray with blue, and black with Solferino; indeed they are to be procured of all shades."

Arthur's Lady's Home Magazine (1864) lists many fashionable colors for stockings, noting that white is only used for "full dress" (ie, very formal attire). Striped and plaid stockings are worn by day, while colored stockings with decorative clocking are used for evening.

|

Blue silk stockings with yellow

"clocks", c.1865, from the Met |

A neat (and unexpected) design appears in these multi-colored silk stockings from 1865: they're made to look like a pair of open shoes with crossed laces!

|

Silk stockings, c. 1865

from The Met |

During the Civil War, women on

both sides of the conflict knitted socks for the army;

songs and poems lauded sock-knitting as a patriotic endeavor.

"Knit socks for the soldiers. Make them to come above the calf of the leg, rib them for three or four inches at the top, make the heels and toes of double thickness." --Healthside, 1861

I have found no period differentiation between "socks" and "stockings", though both terms are used. The surviving examples tend to vary based on leg length, with socks extending about one foot-length above the ankle and stockings 2.5 or 3 foot-lengths. Further investigation is warranted.

Tentative update: a pair of women's, hand-knit

silk stockings, c. 1862, in the MNHS collection has dimensions of 5" by 27.5".

The

Victoria and Albert Museum has a number of very modern-looking socks produced for the Great Exhibition, including these silk and elastic knit socks: