|

| Appliqued Bedcover, 1861, in the Art Institute of Chicago. |

|

| Star of Bethlehem pieced quilt, c. 1840-1850 in The Metropolitan Museum of Art |

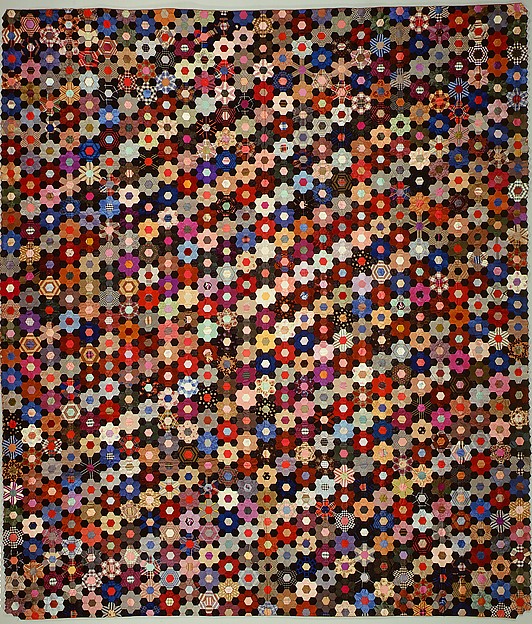

Patchwork, applique, strip, whole cloth, and mixed technique quilts all can be appropriate for the early to mid-1860s. Patchwork designs in use during and just before the American Civil War include Nine Patch, Mill Wheel, Star of Bethlehem, Star of Lemoyne (and another example), Flying Geese, Feathered Star, Wild Goose Chase, Tumbling Blocks, Chimney Sweep/Album/Friendship Chain, Crown, Mariner's Compass, and even simple squares. Log Cabin quilts seem to gain popularity during and after the war. Hexagon or Honeycomb patterns are frequently mentioned in period sources; today this design/technique is also known as "Grandmother's Flower Garden" and "English Paper Piecing". The talented Miss Dories sometimes demonstrates sewing this pattern at events.

|

| Silk hexagon quilt, started 1864, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. |

|

| "Circuit Rider's Quilt", 1862 album quilt, in the Art Institute of Chicago. |

In primary documents, quilts and patchwork are named among the prize categories of agricultural fairs and in exhibitions. The second link includes a separate category for girls under twelve, with a four year-old, a seven year-old, and a five-year-old taking first, second and third place, respectively. A favorite period story of mine, "My Patchwork Quilt" (published in the 1840s), follows the development of a quilt, from the narrator first learning to sew until the work is completed; family anecdotes are tied in by the garment scraps used in the quilt--and a fair amount of social information comes through about the desirability of patchwork quilts, attitudes towards sewing them, how fabrics are acquired, and the process of making and quilting it. Miss Leslie's Lady's House Book (11th ed./1850) has a more matter-of-fact discussion of popular bedcovers, and the different options available. Patchwork designs and projects show up in period magazines. Quilting was even addressed by sewing machine manufacturers.

|

| Patchwork Cushion project in Godey's, 1852 |

|

| Patchwork Pattern from The Lady's Friend, 1864 |

Quilts played their distinctive role in the war; the U.S. Sanitary Commission collected and distributed quilts, blankets, coverlets and comfortables to army hospitals. Quilts might also be gifted to individual soldiers by their friends and relations.

|

| Sanitary Commission album quilt, 1864, by The Ladies of the Fort Hill Sewing Circle in the Smithsonian Museum of American History. |

|

| Star pattern quilt made for the U.S. Sanitary Commission, 1863, by Susannah Pullen's Sunday School class. Now in the Smithsonian. |

For original quilts, you can't beat the International Quilt Study Center and Museum. They also have some articles specifically on Quilts of the Civil War. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Museum of Fine Arts Boston, and The Chicago Institute of Art also have a variety of nineteenth century quilts in their collections (and The Quilt Index has links to even more). The Smithsonian's National Quilt Collection is also worth viewing.

Additionally, Barbara Brackman, noted quilt historian and author, blogs about 1860s quilts at the aptly-named Civil War Quilts; she also writes about antique quilts and reproduction fabric prints at Material Culture. I would particularly recommend her books Quilts from the Civil War, America's Printed Fabrics, and Facts and Fabrications. Elaine Trestain's extensive collection of period quilts provides many of the fabric samples seen in Dating Fabrics: A Color Guide (which also has useful information on period fabric printing methods).

Additionally, Barbara Brackman, noted quilt historian and author, blogs about 1860s quilts at the aptly-named Civil War Quilts; she also writes about antique quilts and reproduction fabric prints at Material Culture. I would particularly recommend her books Quilts from the Civil War, America's Printed Fabrics, and Facts and Fabrications. Elaine Trestain's extensive collection of period quilts provides many of the fabric samples seen in Dating Fabrics: A Color Guide (which also has useful information on period fabric printing methods).